| General Non-Fiction posted May 3, 2022 |

|

A memoir

The Trophy

by J. P. Olesen

The author has placed a warning on this post for language.

The annual fishing trip up to Rainy Lake, Ontario had a long history, and those who made the 10-hour plus drive north varied over the years. When some fishermen couldn’t make it, others were asked to come along. Dad had been on several of them, and started bringing me along as soon as I could properly handle a rod and reel. This was my seventh time up north.

Howard, Bart, Dad, and I made up the group that year. Howard and Bart were my father’s age and had been best friends since high school. The annual trips originally started with them taking little vacations from their married lives by going fishing.

After crossing the Canadian border, we would drive about an hour farther to a place on Rainy Lake called Pearson’s Landing. That was as close as you could drive to get where we fished. From Pearson’s, we travelled by boat, and a runabout from whatever lodge we were staying at would take us the rest of the way.

Boat travel usually took close to 15 minutes. During the ride, I studied the dark green waves on the lake and the weed beds along its shoreline and the seemingly endless rolling forests of pine and birch rising up from the granitic bedrock, and I’d deeply inhale the clean crisp air—and only then, did I truly feel I was finally back in Canada.

Our group stayed at a lodge because the older men came north to fish, not to cook meals or wash dishes or clean the catch brought in at the end of the day. Those were chores that took time away from fishing and the relaxation afterward.

On this trip, we were staying at a place called the Silver Muskie. It was the first time our group had ever been there, and compared to what we were used to, the Silver Muskie was a big step up. This lodge was like a bed and breakfast with all the creature comforts of home, and its woodsy, pine-paneled walls were decorated with impressive-looking mounts of big trophy fish. When you looked at some of them carefully, though, you noticed how their color was fading and their skins were beginning to crack and peel.

We mostly fished for northern pike—one of Rainy Lake's big ambush predators—fish with long, spear point shaped bodies, alligator-like heads, and mouths packed with sharp, spiked teeth. Top notch freshwater game fish, northerns were aggressive as well as ravenous, with trophy specimens weighing more than twenty pounds.

Typically, Howard and Bart fished around Sand Island Falls, which was located at the end of a narrows on the lake. The biggest fish were often caught at the falls when they were hitting, but there were also long intervals of simply casting your lure out and reeling it back when nothing was feeding.

Dad and I usually fished the weed beds close to shore. There were fewer “heehonkers,” the really big fish, but more action because smaller fish would usually be hitting, which kept things interesting. Depending on the fishing, however, we switched back and forth between the falls and the many weed beds scattered around the lake.

On the third day of this trip, a light rain that had been falling tapered off and then stopped by mid-morning. Out on the lake, the water was calm under a heavy gray overcast, and a gentle breeze blowing from the south rippled the water’s surface. The weather was perfect for fishing.

Dad and I nearly finished casting along the length of a little, crescent-shaped weed bed, when a huge boil of water swirled up behind the lure I was reeling in. Hoping whatever slashed at my lure and missed would follow up to hit at it again, I kept reeling, but nothing happened.

“Did you see that boil?” I asked excitedly. “That had to be a big fish!”

The smooth blister of water, created by something turning quickly just beneath the surface, was already spreading out and barely visible. My father, sitting behind me at the stern of our boat, didn't see it. He hesitated a moment before reaching back to shift the little outboard motor into neutral. We tossed our lures near the spot over and over, but due to the boat's momentum, we were casting back at a slight angle. Nothing hit.

“Let's go back for another pass,” Dad said in a reassuring tone that showed he believed me. He reached back to shift the motor into forward and, as quietly as possible, eased the 16-foot aluminum boat out and away so that, whatever it was, wouldn't be scared off.

We circled around to the middle of the weed bed to fish our way back to where I'd seen the water boil up. Nothing hit as we cast out our lures. Finally, when I was directly across from where something had struck at my lure and missed, I managed to cast the orange and gold colored spoon exactly like I had the first time.

Another huge boil of water swirled up as I reeled in the lure. This time, the line went taut, and my fishing pole arched forward sharply. I leaned back, pulling the rod hard to set the treble hook and felt a solid heaviness that didn't even budge.

“I think I've got it,” I said quietly to my dad, who shifted into neutral and killed the motor.

My rod doubled over as a fish rushed away from our boat. Then, what looked like a huge northern pike rose halfway out of the water, mouth open wide, gill covers flared, tossing its head back and forth. I was sure my lure would be thrown.

“Oh, no. No.” I babbled softly, but I heard my father chuckling behind me. He was enjoying the show.

Sliding back beneath the water, it sped off toward the protective cover of the weeds. My reel's drag made a staccato racket as the line was pulled out in a series of jerks. The drag was set way too tight.

I reached forward, fingers fumbling, in front of the reel's spool to loosen the drag. Earlier that morning, I angrily showed Dad how easily my new monofilament line could be snapped by quickly pulling it between my fists. I thought the line was defective, but had nothing else with me to replace it.

With the drag loosened, it sang out smoothly as line peeled off the spool. The fish could have reached the weeds, but surprisingly, it turned around abruptly and raced toward our boat.

Keeping the rod tip high, I reeled as fast as I could. The fish swam past the bow where I was standing. When it felt the pull of my line again, the big northern rose up halfway out of the water, right next to us, shaking its head with a spray of water trying to throw the hook.

“Wow!” Dad cried out and then laughed, but I was too caught-up with the fish and pumped with adrenaline to say anything.

Then, it spun around and rushed back off for the weeds. The drag sang out once more, and I kept my rod tip high, fervently hoping my line wouldn't snap.

The fish stopped just short of the weeds, and I was able to turn it around. I took back line, lifting the rod tip high to pull in, and reeling quickly as I lowered my pole. The big northern twisted sideways in the water or lifted its head just above the surface, shaking its jaws still trying to throw the hook, but kept moving closer to ease the pull from the line.

“Ready with the net,” I said anxiously as it came toward the boat.

Gently, I coaxed the fish up near the water's surface, guiding it toward my father, who was already holding the dip net. The spoon was hanging outside its mouth, but I couldn't make out how solidly the fish was hooked. I'd never seen a bigger northern pike in my life, but something didn't look quite right. Unlike northerns, this fish had an unusual, silvery color.

“I think it’s a muskie,” I said over my shoulder to my father.

Dad tried netting the fish. But when its head was well inside the dip net, the fish spooked, spun around with a big splash, and rushed away from the boat.

“Oh God, no!” I cried out, because I was sure my lure would be snagged in the net's mesh and torn out. Fortunately, it wasn't.

This time, the big fish only swam halfway toward the weeds. It was tiring. I reeled in again as it twisted and turned in the water. Soon, it hung motionless, suspended upright, close to our boat and just beneath the water's surface.

Dad eased the dip net into the water. The fish was too long to fit inside, so he kept sliding the net forward as he lifted. Its bulk doubled up in the mesh as my father slid everything forward and up, then over the side of our boat and down onto the hull in one fluid motion.

“Hoowee!” my father shouted as it hit the bottom of the boat. The big fish still had plenty of fight left and flopped wildly back and forth, knocking over my tackle box with a smack of its tail.

“What a fish!” I cried out. “That was a terrific job with the net, Dad!”

My father and I smiled at each other happily across the length of the boat. Then, I half-sat, half-collapsed onto my seat at the bow, still shaking from adrenaline, and stared at the big fish with a little awe. It was definitely a muskie and not a northern. Muskellunge, or muskie for short, closely resembled northern pike and had the same habits, but muskies were far less common, fought harder, and grew even bigger.

This muskie’s back was at least five inches across and colored dark green. Its sides were a greenish-silver with subtle, vertically arranged, olive-colored bars and spots. Its belly was white, the fins brownish red, and its big forked tail was colored like the fins and pointed at the tips. It was a long, heavy, well-proportioned fish.

After the muskie and I settled down, I stood up to untangle it and my lure from the net. The fish had been solidly hooked in the side of its mouth, but the treble hook was easily removed using a pair of long-nose pliers. I had to be a little careful, though, because of its mouthful of needle-like teeth—some of them half an inch long. Every once in a while, northerns and muskies could slash at your hand when you unhooked them.

It was a beautiful trophy muskie, and I'd never seen a bigger fish caught by anyone during our trips to Rainy Lake. There was just one snag. Fishing season for muskies in Ontario opened on the third Saturday of June. That was more than two weeks away. Unless we wanted to violate the regulations we fished by, the muskie needed to be released.

Then, things really went sideways. The little Zebco scale in my tackle box was designed for fish weighing up to eight pounds, and its measuring tape extended only 24 inches. It was for smaller game fish like smallmouth bass or walleye. My father's scale went up to 25 pounds, but that bottomed out when he tried weighing the fish. Worst of all, Dad's 35mm camera, which accompanied him nearly everywhere on these trips, had accidentally been left behind at the lodge.

“Let's find Howard and Bart at the falls,” Dad said. “Maybe they'll have a camera and a heavier scale.”

My father revived the outboard with one quick, stronger-than-usual tug on the starter rope. Just before sitting down to shift the motor into forward, I heard him mutter, “Goddammit, I'd give my left nut if that fish was a northern.” He'd spoken calmly a moment before, but was deeply frustrated about leaving the camera behind, our scales being too light, and the muskie being out of season. Dad would've loved having a fish that size mounted for me as a trophy.

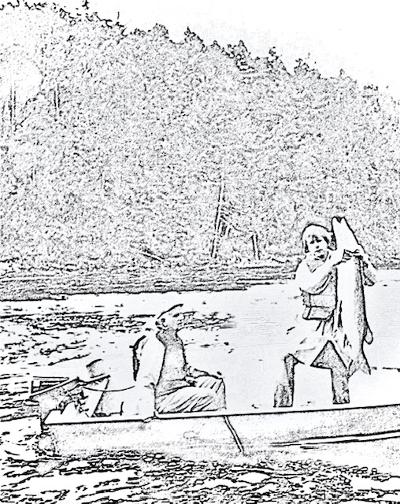

As we sped up the narrows toward the falls, I gazed at the muskie lying with its head curving up one side of the hull and its tail curving up on the other. I wanted to remember what the fish looked like. It might be all I'd keep.

The falls was only a couple of minutes away. I knew Howard and Bart would be there because we watched them travel that way earlier in the morning. We’d been heading there, too. Fishing the little, crescent-shaped weed bed had been a whim of my father's. Howard and Bart couldn't pass back through the narrows without us seeing them. I just hoped they packed a camera and a heavier scale.

Sand Island Falls emptied into Rainy Lake through a gap in the bedrock about 25 feet wide and seven feet high. A huge volume of water forced its way through that gap, and a lot of big predator fish congregated around the oxygen-rich water to feed on smaller fish killed or crippled going over the falls. The area was also a spawning ground for bait fish.

As we approached, I spied Howard and Bart in their boat off to the left casting around the margins of the fast-moving water. Bart noticed us and waved cheerfully. As Dad and I pulled alongside, he stood to grab our boat and made the funny little call whose ending was clipped and dropped down a notch in pitch. It was a greeting everyone else enjoyed imitating during our fishing trips.

“Oh-o!” he called out with a big smile. “How's the fishing men?” Then, an instant later, when he looked in our boat, “Man-oh-man, what a heehonker! Which of you caught that?” Dad and I told them our predicament with the muskie.

Fortunately, Bart carried a little Instamatic camera in his coat pocket, and Howard packed a longer measuring tape inside his tackle box as well as a scale that could weigh fish up to 30 pounds. Howard, a very nice, soft-spoken guy with an earthy sense of humor was an accountant, and he meticulously measured the fish's length at 48 inches. When he first weighed the muskie, Howard's scale read 27 pounds. The second time, his scale bottomed out like my father's.

“That muskie is easily a 30-pound fish,” Bart said matter-of-factly.

Bart had a 25-pound northern pike mounted on the wall of his office. I'd seen it one summer when, as a barefoot kid riding my bicycle past his business, I dropped in to say hello. He knew what he was talking about when estimating weight for a fish this size.

Everyone agreed that 30 pounds was more accurate and left it at that. I kept quiet and listened. Whatever they thought was okay by me. After the muskie was weighed, Bart took several quick photos with the Instamatic.

We all knew that muskies, though terrific fighters, were relatively delicate fish that couldn't survive long out of water. We weren't sure why, only that they didn't. From the time Dad and I boated the muskie—met Howard and Bart at the falls, measured, weighed, and took photographs—to the time the fish was back in the water being revived was fewer than 15 minutes.

Cradling it alongside our boat, I slowly rocked the big fish forward and back so water could flow over its gills. When the muskie recovered, I let go, and with a small smile no one else noticed, watched it slowly swim out of sight. I remembered how some of the mounted fish looked hanging on the walls back at the lodge. This was better.

Now, more than 40 years later, the older fishermen on that trip have passed on—including my father. I think of them often and fish with the rod, reel, and most of the tackle I used back then as well as my dad's fishing gear. Catching that muskie was one of the high points in my life, and when I released it up at the falls, I saw in that moment that maybe some things happened as intended. If so, the implications were profound.

My trophy is a few photographs yellowed by age and the memories of that day so long ago. I'm good with that.

Non-Fiction Writing Contest contest entry

Recognized |

Had it not looked a little odd wrapped around the illustration, I would have included the following epigraph for my story:

The question is not what you look at, but what you see. ~ Henry David Thoreau, Journal, 5 August 1851

Pays

one point

and 2 member cents. The question is not what you look at, but what you see. ~ Henry David Thoreau, Journal, 5 August 1851

You need to login or register to write reviews. It's quick! We only ask four questions to new members.

© Copyright 2025. J. P. Olesen All rights reserved.

J. P. Olesen has granted FanStory.com, its affiliates and its syndicates non-exclusive rights to display this work.